-

Premier League is back: Analyzing busy Boxing Day slate of action - December 27, 2022

-

3 thoughts from Argentina's win over France in legendary World Cup final - December 21, 2022

-

Even in a World Cup of twists and turns, it came down to Messi and Mbappe - December 20, 2022

-

Team of the tournament: Best XI at 2022 World Cup - December 19, 2022

-

22 unforgettable moments from the 2022 World Cup - December 19, 2022

-

Messi finally wins World Cup as Argentina dethrones France in epic final - December 19, 2022

-

World Cup final preview: Key questions, prediction for Argentina vs. France - December 17, 2022

-

Why Qatar's sportswashing project is surviving World Cup controversies - December 17, 2022

-

How France held off lionhearted Morocco to make 2nd straight World Cup final - December 16, 2022

-

France's World Cup title defense once seemed unlikely. Now, it's near reality - December 15, 2022

Why Qatar's sportswashing project is surviving World Cup controversies

The 1934 World Cup was dictator Benito Mussolini’s propaganda showpiece.

The Fascist anthem “Giovinezza” was sung at each game. The regime’s flags flew. Even FIFA’s commemorative postage stamps included Fascist insignia. Mussolini, whose appearances at matches were rapturously received, reveled in showcasing the might of Italy in front of locals and visitors from abroad. The Azzurri won the tournament with the help of dubious refereeing decisions.

The term “sportswashing” is widely believed to have existed for less than a decade, but the practice itself is much older.

“Using sport to launder your nation’s reputation or to turn attention away from bad things your government is doing has a long history of working,” University of Guelph history professor Alan McDougall, who studies sportswashing, told theScore. “I think that’s something we don’t want to face up to, but history tells us that’s true.”

Qatar has arguably undergone the most expensive sportswashing project in history. Research from the BBC found the cost of the 2022 World Cup reached $220 billion before the tournament kicked off in November – a total over three times larger than the previous eight World Cups combined.

The result of this vast expenditure is seven brand-new stadiums plus one thoroughly renovated venue, countless hotels, a transit system, roads, and other infrastructure. Another outcome of Qatar’s World Cup is a level of media scrutiny that the Gulf nation appeared unprepared for when it was awarded the event in 2010.

Human rights groups estimate thousands of migrant workers died while constructing projects relating to the tournament, while many more suffered abuses such as injury and wage theft. Members of the LGBTQ+ community were “arbitrarily” detained and beaten by Qatari security forces in the lead-up to the World Cup, according to Human Rights Watch, and there were accounts of match-goers being denied entry into stadiums while wearing clothing or carrying personal items featuring designs vaguely resembling the rainbow flag.

Qatar is accused of deliberately using a major international sporting celebration to conceal these problems. But, unlike sportswashing projects of the past, Qatar’s plan seems to have staying power. The World Cup isn’t one rudimentary tool designed to fortify a shady regime – it’s just one part of a long-term aim to raise the reputation and ambitions of a tiny, oil-rich state.

“They’re in it for the long haul. Earlier examples of sportswashing are bloody regimes that are using football as a fig leaf to cover up for a nasty dictatorship – Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany, the Argentine military dictatorship,” McDougall said, also referring to the 1936 Olympics and 1978 World Cup. “Whereas here you’ve got these authoritarian, wealthy, monarchical regimes which are using sports very strategically and very savvily, I would say, to really build a nation’s brand.”

Brand wars

Qatar isn’t alone in crafting this game plan. Its Gulf neighbors are also trying to boost their respective images through sports, and money isn’t much of an obstacle in a region where fossil fuels were discovered throughout the 20th century.

“Oil and gas have done a lot of things to the Gulf, but one thing that they’ve done to all these countries – like the Emirates and Qatar and Kuwait and Saudi Arabia – is that they’ve given the governments great ambition that they couldn’t have had before. One of those ambitions is to be influential players on the world stage,” said Sean Yom, an associate professor of political science at Temple University and expert on Middle Eastern affairs.

“There has been growing recognition by the governments of these countries that hosting large, prominent, famous competitions that take worldwide relevance can instantly skyrocket the visibility and the prestige of their so-called national brand,” he added.

Before the World Cup graced the Arab homeland for the first time this winter, the Gulf’s influence over football was already significant.

French champions Paris Saint-Germain are owned by Qatar Sports Investments. The City Football Group, which is majority owned by a member of the Abu Dhabi Royal Family’s private equity company, presides over English giants Manchester City – who won their fourth English title in five years last season – while holding stakes in 10 other clubs across Australia, Asia, Europe, North America, and South America. The sovereign wealth fund of Saudi Arabia commenced an ambitious project with Manchester City’s Premier League rivals Newcastle United in 2021 and, away from football, has notably rocked one of the globe’s most traditional sports with the advent of LIV Golf.

The biggest sports events – namely the Olympics and World Cup – have also become more accessible to the Gulf and other parts of the world desperate to improve their international standing. The 2026 World Cup in North America increasingly stands out as an anomaly since the competition has traversed more diverse regions over the past 20 years, like Japan and South Korea’s joint venture in 2002, South Africa in 2010, Russia in 2018, and Qatar in 2022. Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city, finished only four votes adrift of Chinese capital Beijing in a head-to-head bidding race for the 2022 Winter Olympics.

The costs and other unsavory aspects of hosting such events are increasingly unappealing to nations in Europe and North America, forcing the biggest sports organizations to look elsewhere for venues and income.

“Democracies are having a hard time, for economic and environmental reasons, in putting forward cases for hosting an Olympics or a World Cup,” McDougall explained. “So, I think the field might be open for years for petro-states to be the only people who’d be willing to host.”

The Gulf rivalries obviously extend beyond each state’s sporting outreach. Qatar was effectively isolated in 2017 when Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates created a “blockade.” The severing of diplomatic relations with Qatar meant there was an air, land, and sea embargo on the nation, with its neighbors accusing the World Cup host of financing terrorism and strengthening its ties with Iran.

Although the four countries reversed course early in 2021 and vowed to rebuild relations with Qatar, jealousy and rivalries were still rampant as the Gulf states’ efforts to enlarge their imprint on regional and global affairs continued unabated.

Given that Qatar’s construction and commercialization boom largely occurred in this century, its rise to challenge Saudi Arabia’s status in the Arab world has irritated plenty of those living across Qatar’s only land border. A Saudi insult for Qatar is to sneeringly describe it as a “big fart” that hangs off Saudi Arabia, emitting lots of unpleasant gas, but Yom believes this jibe is aired by the more “chauvinistic” sections of society.

The heated relationship between Qatar and its neighbors made developments during the World Cup more surprising. In a deliberate display of unity, Qatar’s emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani, and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia held hands during the opening ceremony of the World Cup. Each leader was also pictured wearing a scarf bearing the colors of the other’s flag.

The bonds appear stronger among fans at the tournament as well. Many Saudis are proud of the World Cup getting its first Arabic facelift despite it not being in their country, while plenty of Qataris delighted in Saudi Arabia’s surprising win over Argentina in its group opener. This apparent accord with Saudi Arabia can only be a good thing for Qatari diplomacy – even if it’s just to keep its enemy closer.

Success ‘turns a blind eye to everything’

The outrage at Qatar’s human and labor rights practices was at fever pitch before the World Cup kicked off. It seemed every media outlet ran stories chastising Qatar’s blatant sportswashing scheme – this one included – while FIFA urged the 32 competing teams to “focus on football” rather than political and social concerns. The deaths and abuses were in danger of forever damaging Qatar’s World Cup legacy.

But then the tournament started.

“If the idea is to put your country on the map through spending a large amount of money to host a big sports event, then Qatar has succeeded despite the controversies,” McDougall said.

McDougall wasn’t surprised at how the criticism cooled while an intriguing tournament pinched the spotlight. Sporting success “turns a blind eye to everything,” he shared, citing the example of Newcastle’s takeover by Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund. Initially, the deal for the English club was shrouded in controversy due to the Saudis’ human rights issues; the criticism hasn’t completely subsided, but praise of manager Eddie Howe and some of the Magpies’ expensive recruits, like Brazilian midfielder Bruno Guimaraes, is beginning to dominate the narrative. The Saudis’ success story in England is gradually nudging the regime’s grim practices at home into the background.

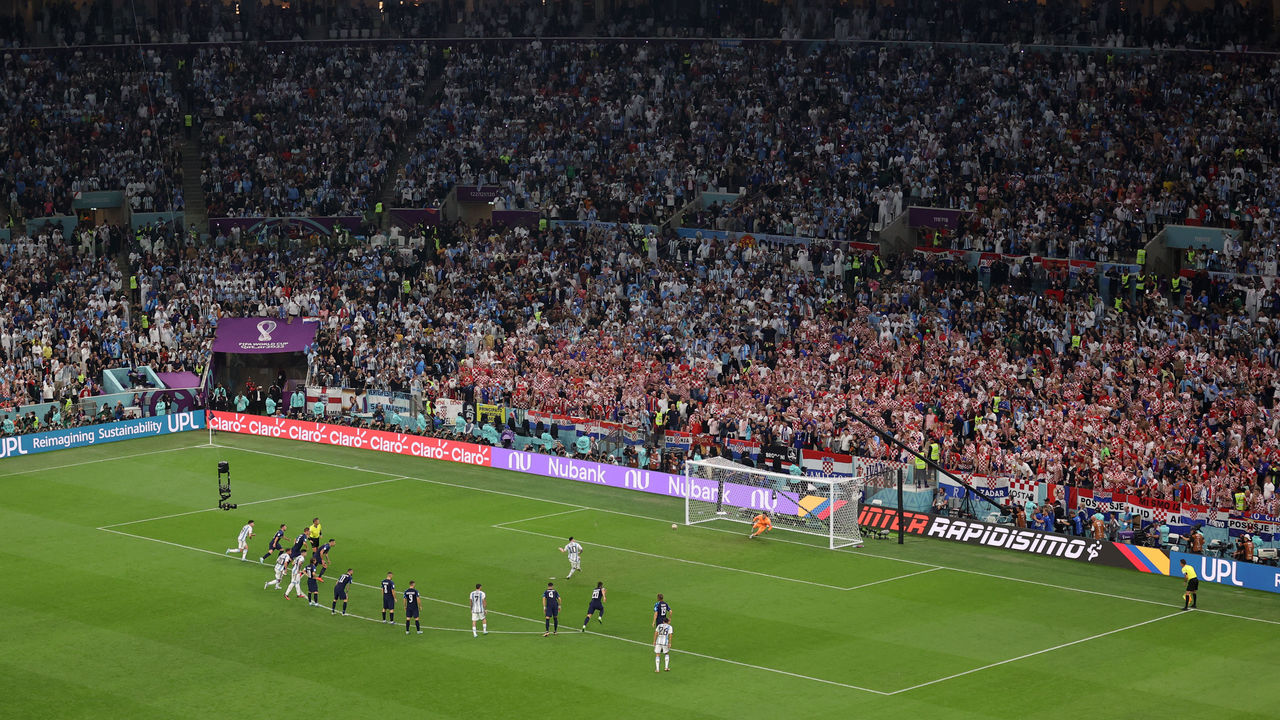

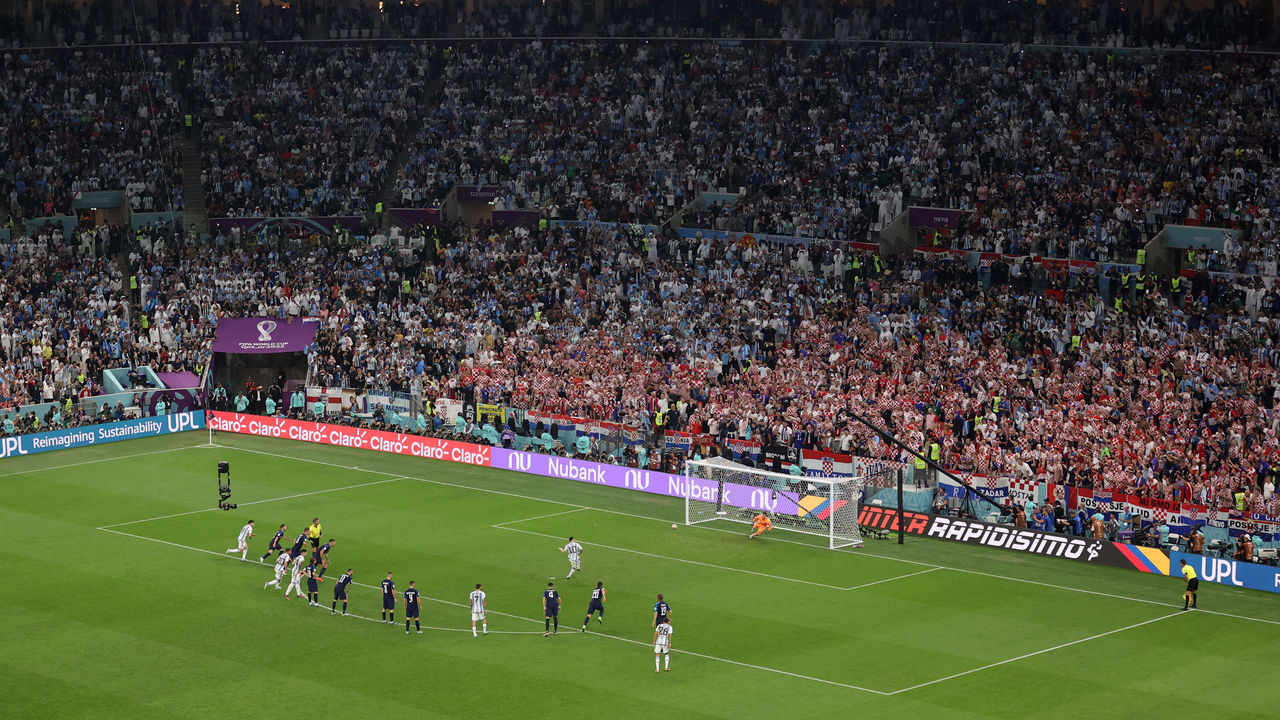

And could there be a bigger smokescreen for Qatar’s well-documented problems than concluding an exciting tournament with Sunday’s glittering World Cup final between Lionel Messi’s Argentina and Kylian Mbappe’s France?

“The average casual football fan 10-15 years from now is not going to remember the media hubbub over migrant rights and human rights violations in Qatar this year, but they will remember, for instance, the Moroccan breakthrough in Qatar in 2022,” Yom told theScore. “They’ll remember the time the World Cup was in the Middle East, they’ll remember the extraordinary logistics that may have gone into this event. I think that is the enduring legacy that Qatari officials want from the World Cup, and I think they’ll get it.”

Unlike the World Cup in Mussolini’s Fascist Italy, Qatar isn’t trying to attract tourism or flex its military muscles. Even business isn’t a concern – its gas will remain a coveted and extremely profitable asset. The World Cup was simply an opportunity for Qatar to showcase why the modern civilization it fashioned on a dusty peninsula is capable of staging an event for everybody. The deaths and the treatment of the LGBTQ+ community will sadly be overwhelmed by the prominent conversations about the final, and they won’t be among the main talking points when club football restarts just a few days later.

Instead, the World Cup will be neatly boxed away, available for any sports fan to pull off the shelf and peer into whenever they like. A product for the world to enjoy, with love from Qatar.